The Bible as Literature - By John Eppel

THE BIBLE AS LITERATURE - notes by John Eppel

Zimbabwe Academy of Music, Bulawayo (25-27 November 2013)

[With a focus on imagery, allegory, and poetry]

INTRODUCTION

Before I begin these talks, I want to make it very clear that I am in no way challenging the belief that the Bible is the inspired word of God. Spiritual ‘truth’ is just as important in peoples’ lives as scientific ‘truth’, historical ‘truth’, philosophical ‘truth’, and aesthetic ‘truth’. Whenever I use the word ‘truth’ I put it in inverted commas to suggest my own uncertainty in this matter. The three areas I have chosen to talk about overlap each other quite considerably, so I want you to think of this as one talk separated into three sessions rather than three separate talks. My primary source is the Bible and my secondary sources are The Great Code: The Bible and Literature by Northrop Frye, and The Bible as Literature: An Introduction by John B. Gabel, Charles B. Wheeler, and Anthony D. York.

One of the challenges of reading the Bible is that words have passed through three modes or phases: the thaumaturgic, the metonymic, and the scientific. The third phase rarely occurs in the Bible, yet it is the phase that you and I are in right now, where inductive reasoning is dominant. In this phase the key word is ‘description’. We describe something by saying it is like this or that, not in the sense of a simile, which has a metaphorical effect, but in the literal sense. This plant produces spores instead of seeds therefore it is like a fern. We go from the particular to the general. If we observe a number of aspects of this plant that continue to liken it to a fern, we may go on to deduce that it belongs to the fern family, which may, in years to come, turn out to be a wrong deduction, since the process of science is one of disproving. Euclid was partly disproved by Newton who was partly disproved by Einstein who is partly being disproved by contemporary scientists.

The two phases of language in the Bible are thaumaturgic (miraculous), and metonymic (reductive), and they have a dialectical relationship with each other. The controlling figure of speech in the first phase of indwelling (or immanence) is the strong metaphor where the binary, characterised by the simile, ceases to exist. God is not like this or that, God is: ‘I am that I am’. When God said let there be light, there was light. This is the Logos, the word made flesh. This phase has its links to magic (the demonic counterpart of religion) where words like ‘abracadabra’ and ‘hocus-pocus’ can immediately bring about happenings. In this phase, metaphor is not recognized as such. It doesn’t seem to be; it is. Subject and object have merged completely. Like the Roman Catholic communion service, the bread and the wine, the body and the blood, are One. This is what I call a strong metaphor. For Protestants, the bread and the wine are put for the body and the blood. This is what I call a weak metaphor, and weak metaphors, or metonymies, or similes, or allegories or analogies or typologies belong to the middle, threshold phase. It is in this phase that lyric poets operate in their attempts to transcend Cartesian dualism, and where teachers of the humanities operate in their attempts to elucidate morality. Quite a few strong metaphors have survived in the current scientific phase. One example is ‘sunrise’ and ‘sunset’. We don’t even think of these words as metaphorical until someone points out that it is the earth and not the sun that moves. Another example is the ‘law’ of the jungle. There is no ‘law’ in nature, yet the phrase comes to us as literal, not metaphorical. Ironically then, our so-called dead metaphors are strong metaphors- indwelling, inherent in the words.

It seems to me that, in order to read the Bible as the inspired word of God, we need, by some process, meditation or prayer –or computer-generated virtual reality - to return to the first phase or mode of language. Isn’t that what believers mean when they tell sceptics who nit-pick the holy text that they are not reading it in the right spirit? My reading of the Bible, for the purpose of these talks, is as a work of literature; consequently I will stay put in the third, descriptive, phase.

BACKGROUND TO THE KING JAMES BIBLE

I have chosen the Authorised Version as my text because it is, I am told, the most literary of the numerous translations. Here is a bit of background to the English Bible.

We owe the first complete English translation of the Bible to a clergyman called John Wyclif (1324 – 84). He was declared a heretic after his death, and his body was exhumed and destroyed. When William Tyndale (1484 – 1536) decided to attempt a translation he had to get permission from the Bishop of London. Permission was denied him so he went to Germany to begin his work. Here he translated the New Testament from the Greek, and the Old Testament, with help from Miles Coverdale, from the Hebrew. Tyndale was arrested by the papal authorities who accused him of heresy. He was strangled and burnt. Coverdale managed to escape.

The so-called Coverdale Bible formed the basis of the version, which was authorised by King James the First of England. In 1604 he appointed about fifty scholars to produce a definitive English version of the Bible. The work was completed in 1611, five years before Shakespeare’s death. In 1970 the most accurate translation of the scriptures was published as The New English Bible. What it gained in scholarship, it lost in beauty. The AV is a masterpiece of simplicity, using no more than 6 000 words against Shakespeare’s 30 000. Today there are more than a million words in the English language.

THE UNITY OF THE BIBLE

If you read the Bible outside the unifying idea that it is the inspired word of God, you find what appears to be a chaos of disconnected texts of multiple unknown authorship, altered and rearranged over hundreds of years by unknown editors, or redactors; but if you look at it from a literary point of view, you start finding a number of unifying factors.

In the first place it has a beginning and an end, a prerequisite for stories. It begins with the creation and ends with the apocalypse. It also has a plot: the eternal conflict between good and evil. This narrative unity is enhanced by certain recurring images, for example, water and trees. In Genesis we have the tree of life and the river that ran out of Eden; in the final chapter of Revelations we have: ‘a pure river of water of life, clear as crystal, proceeding out of the throne of God and of the Lamb … and on either side of the river, was there the tree of life’ [22, 1-2]. In literary terms, the Bible is a ‘divine comedy’; that is because it ends happily, not because it isn’t serious.

Another unifying effect is the typological structure of the Bible where significant incidents in the New Testament are fulfilments of Old Testament proverbs and prophecies. For example Paul’s axiom, ‘The just shall live by faith’ [Romans 1:17] is an echo of Habakkuk’s words: ‘Behold, his soul which is lifted up is not upright in him; but the just shall live by his faith’ [2:4]. And Jesus’ all too human cry on the cross: ‘My God, why hast thou forsaken me’, can be found in Psalm 22: ‘My god, my God, why hast thou forsaken me? Why art thou so far from helping me, and from the words of my roaring? [22:1]. What happens or what is said in the Old Testament is a ‘type’ of what happens in the New Testament. In the latter it becomes an‘antitype’. So Christian baptism is the antitype of the saving of mankind from Noah’s flood, and Christ’s resurrection is an antitype of Adam’s Fall. Jesus himself draws our attention to the typological structure of the Bible when he reminds his not very perceptive disciples: ‘These are the words which I spake unto you, while I was yet with you, and that all things must be fulfilled, which were written in the law of Moses, and in the prophets, and in the Psalms, concerning me’ [Luke 24:44].

A third unifying factor is its paratactic style, a style characterised by commands and exhortations linked by the co-ordinate ‘and’. You could call it an oratorical style influenced by the original Hebrew in the Old Testament and the original Greek in the New. We’ll get a taste of it when we read the Creation stories and try to ascertain the good fruit.

Every divine feature of the Bible has its demonic counterpart. For every good there is an evil. The counterpart of the bridegroom and bride figures is the great whore, Babylon, mistress of the antichrist. The counterpart of Jerusalem is the Tower of Babel. The demonic side of animal imagery are beasts of prey like wolves. This antithetical pattern also contributes to the unity of the Bible.

Finally, the ultimate unifier is Christ himself, since, as prophet, priest, and king, he is the hero of the entire Biblical narrative.

Biblical Imagery

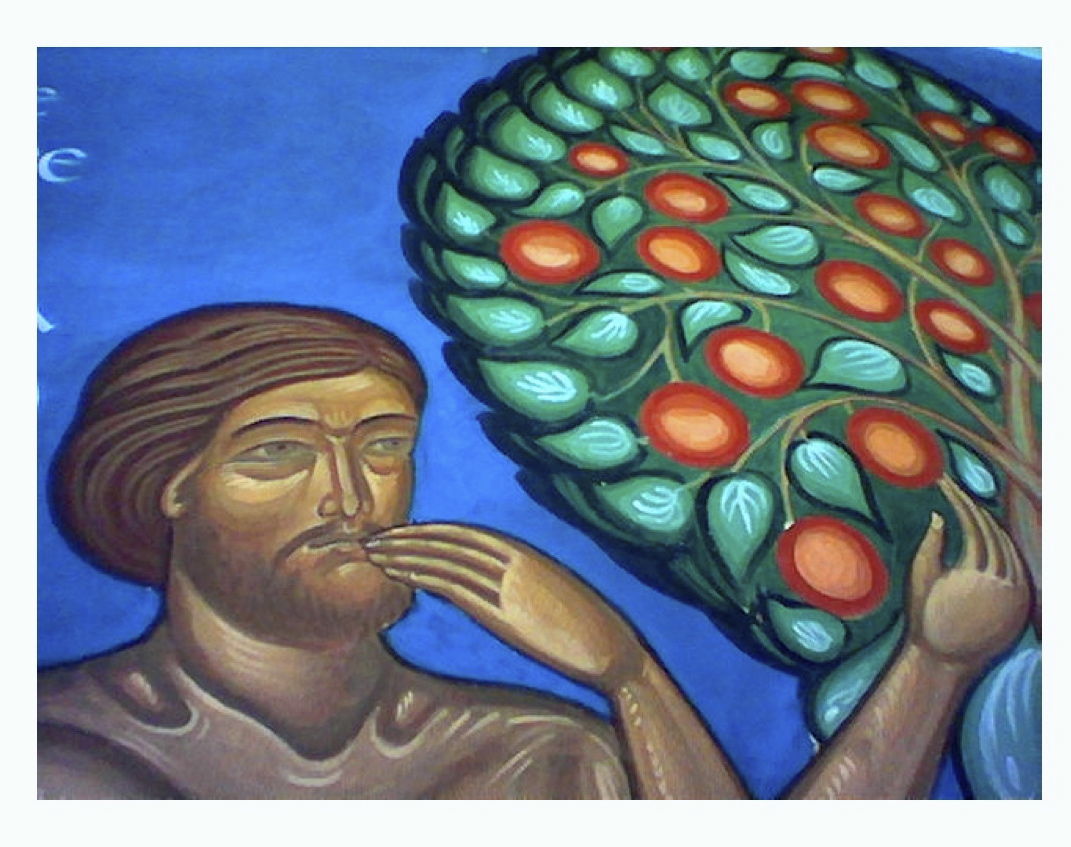

The imagery of the Bible is strongly influenced by it geographical location: great rivers running through desert to the sea. The oases with their fountains and fruit bearing trees are particularly influential. Indeed, one can imagine the Garden of Eden to be an oasis of some kind. For the purposes of this paper, I am going to examine just two images: trees and fruit.

The most enigmatic of all Biblical trees are the Tree of Life, the Tree of Good and Evil, and the cross (a stylised tree) upon which Jesus was crucified. Trees and fruit are organically and symbolically connected. The most enigmatic of the Biblical fruits are the wicked fruit in Genesis, evermore associated with Eve and, by extension, womankind; and the good fruit in the Gospels, Christ on the cross? There. I’ve given it away.

The tree is one of humankind’s most powerful symbols because from it comes the notion of the universe in a state of perpetual regeneration, simultaneously living and dying. With its roots and its branches, it unites sky and earth, or heaven and hell, or body and soul. When we meditate on a tree our doors of perception are opened so that everything appears to us as infinite. All the elements come together in the tree: there is water in their sap, there is air in their leaves, there is earth in their roots, and there is fire in their branches. The tree is a quintessence. Furthermore, the gap between the trunk and the canopy reveals a fork or Y shape, which symbolises the paradox of oneness and duality.

Fruits that split and contain many seeds, like pomegranates and figs, are symbols of fertility, denoting the vulva, although Christian mysticism has transposed the pomegranate, for example, to the spiritual plane. The roundness of the fruit expresses the eternity of God; its sweet juice, the bliss of the soul… but more about allegory in our next talk.

Traditionally the forbidden fruit of Genesis is thought of as an apple but that is unlikely since apples are associated with more temperate zones. This probably came about because the Latin word for apple is malum, which is also the word for evil. You can see where the phrase Adam’s apple comes from.

Pomegranates and figs grow in the region. Adam and Eve hide their nakedness with fig leaves. Pomegranates connect us with the ancient Greek story of Persephone where she is tempted by the god of the underworld to eat six seeds, and that forces her to stay in Hades.

Other claimants to the forbidden fruit have been grapes (associated with drunkenness) and mushrooms (associated with hallucinations).

THERE FOLLOWS A CLOSE READING OF GENESIS, CHAPTERS 1 TO 3

* *

Biblical Allegory

Allegory is authoritarian. It doesn’t suggest the ‘truth’, as other kinds of metaphor do; it demands the ‘truth’. Metaphorical comparisons are selective. If I say my love is a rose, I don’t expect you to think of thorns, leaves, roots, aphids… I expect you to think of colour, petals, and scent.

Allegorical comparisons, on the other hand, are all inclusive: the thorns, the roots, the leaves, the diseases, will find their parallels in the girl of my dreams.

An allegory is an entertaining surface story that is paralleled by a usually moralistic submerged story. The ostensible story is on the surface; the actual story is below the surface. The parables of Jesus are brilliant examples of short allegories.

Here is a diagram of the allegory of the vineyard in Matthew 21: 33-43:

ACTUAL - Israel – prophets – loyalty – Jewish leaders – Jesus – Gentiles

| | | | | |

OSTENSIBLE – vineyard - servants – produce – tenants - owner’s son – other tenants

This insistence on finding comparisons for every little detail (more by readers than the writers, I might add), gives allegory a linear structure that can be very long indeed. Think of John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress or Herman Melville’s Moby Dick.

When the author of Ephesians [6:13] calls upon us to ‘take up God’s armour’ against the devil, he is using a metaphor, implicitly comparing God’s virtue to soldiers’ protective gear; but he doesn’t stop there: he parallels loins with truth, the breastplate with righteousness, feet with peace, the shield with faith, the helmet with salvation, and the sword with the word of God. Here the writer is being deliberately allegorical, giving the reader no space to invent his own interpretations. This is straightforward stuff, but what about the astonishing historical allegory of Ezekiel, Chapter 17? Let’s look at the first six verses.

THE FIRST EAGLE

‘And the word of Jehovah came unto me, saying, Son of man, Put forth a riddle, and speak a parable unto the house of Israel; and say, Thus saith the Lord Jehovah: A great eagle with great wings and long pinions, full of feathers, which had divers colours, came unto Lebanon and took the top of the cedar: he cropped off the topmost of the young twigs thereof, and carried it unto a land of traffic; he set it in a city of merchants. He took also of the seed of the land, and planted it in a fruitful soil; he placed it beside many waters; he set it as a willow tree. And it grew, and became a spreading vine of low stature, whose branches turned toward him, and the roots thereof were under him: so it became a vine, and brought forth branches, and shot forth twigs.’

The author explains this part of his allegory in verses 12 – 14. He says, ‘Say now to the rebellious house, know ye not what these things mean? Tell them, Behold the king of Babylon is come to Jerusalem, and hath taken the king thereof, and the Princes thereof, and led them with him to Babylon. And hath taken of the king’s seed, and made a covenant with him, and hath taken an oath of him: he hath also taken the mighty of the land: That the kingdom might be base, that it might not lift itself up, but that by keeping of his covenant it might stand.’ But he is not absolutely specific like the author of Ephesians. Consequently readers’ interpretations have no check. Here is one, which I found on the internet:

The analogy here is called both a riddle and a parable. Indeed, it is both. How the clipping from the cedar became, first ‘as a willow tree,’ and later as a vine is not explained.

The first eagle here represents the king of Babylon, Nebuchadnezzar. ‘The great eagle' mentioned here is from the Hebrew [~neser], which actually means the griffon vulture; and that is the basis for the Revised Standard Version rendition here. It appears to us that a vulture is more in keeping with the personality of Nebuchadnezzar than an eagle!

‘The cedar of Lebanon ...’ (Ezekiel 17:3). is a reference to the land of Palestine.

‘The topmost of the young twigs thereof ...’ (Ezekiel 17:4). refers to the young king Jehoiachin.

‘The seed of the land which was planted ...’ (Ezekiel 17:5). is a reference to Zedekiah.

‘Fruitful soil ... many waters, etc....’ (Ezekiel 17:5). These express the beauty and fertility of Palestine.

‘Land of traffic ... city of merchants ...’ (Ezekiel 17:5). These indicate Babylon, to which Jehoiachin and the first company of deportees were carried away.

‘And the roots thereof were under him ...’ (Ezekiel 17:6). This means that Zedekiah's dependence upon Babylon would not change. The earlier statement here that ‘his branches turned toward him (the king of Babylon)’ indicates the same thing. As long as Zedekiah remained true to his sworn allegiance to the king of Babylon, all went well with the kingdom; but his rebellion brought on the swift and total destruction of Jerusalem.

[Coffman’s commentaries on the Bible]

We are also given an explanation in Nathan’s allegory for King David. It is signalled in the words, ‘And Nathan said to David, Thou art the man’ [2 Samuel 12:7]. This allegory has the powerful literary effect of David unwittingly condemning himself:

12 Then the Lord sent Nathan to David. And he came to him, and said to him: “There were two men in one city, one rich and the other poor. 2 The rich man had exceedingly many flocks and herds. 3 But the poor man had nothing, except one little ewe lamb which he had bought and nourished; and it grew up together with him and with his children. It ate of his own food and drank from his own cup and lay in his bosom; and it was like a daughter to him. 4 And a traveller came to the rich man, who refused to take from his own flock and from his own herd to prepare one for the wayfaring man who had come to him; but he took the poor man’s lamb and prepared it for the man who had come to him.”

5 So David’s anger was greatly aroused against the man, and he said to Nathan, “As the Lord lives, the man who has done this shall surely die! 6 And he shall restore fourfold for the lamb, because he did this thing and because he had no pity.”

7 Then Nathan said to David, “You are the man! Thus says the Lord God of Israel: ‘I anointed you king over Israel, and I delivered you from the hand of Saul. 8 I gave you your master’s house and your master’s wives into your keeping, and gave you the house of Israel and Judah. And if that had been too little, I also would have given you much more! 9 Why have you despised the commandment of the Lord, to do evil in His sight? You have killed Uriah the Hittite with the sword; you have taken his wife to be your wife, and have killed him with the sword of the people of Ammon. 10 Now therefore, the sword shall never depart from your house, because you have despised Me, and have taken the wife of Uriah the Hittite to be your wife.’ 11 Thus says the Lord: ‘Behold, I will raise up adversity against you from your own house; and I will take your wives before your eyes and give them to your neighbour, and he shall lie with your wives in the sight of this sun. 12 For you did it secretly, but I will do this thing before all Israel, before the sun.’”

13 So David said to Nathan, “I have sinned against the Lord.”

We learn from his letters, the earliest part of the New Testament to be composed, that Paul also read the Jewish scriptures allegorically. He can be quite condescending about the literal sense, for example, in 1 Corinthians, 9:9 – 10: ‘For it is written in the law of Moses, Thou shalt not muzzle the mouth of the ox that treadeth out the corn. Doth God take care for oxen?

‘Or saith he it altogether for our sakes? For out sakes, no doubt, this is written: that he that ploweth should plow in hope; and that he that thresheth in hope should be partaker of his hope’.

The question has frequently been asked why a teacher like Jesus, most of whose followers would have been uneducated, would have used a method which confused as much as it enlightened, and there are scholars who argue that his parables have been allegorised by New Testament authors. For example, the parable of the sower in Mark does not seem to fit the allegorical interpretation that has been added to it. There is a change of focus from the act of sowing the seed to what happens to the seed after it has been sown. The sower, suddenly, is nowhere to be found; the seed, representing the gospel, the Word, becomes paramount.

THERE FOLLOWS A CLOSE READING OF SONG OF SOLOMON

Biblical Poetry

About one third of the Old Testament is poetry, but translators, conditioned by poetic forms like rhyme and metre, which don’t exist in Hebrew prosody, were unable to distinguish between what was poetry and what was prose. Only the psalms were acknowledged as poetry because they were presented as songs to be sung. We have to think of Hebrew poetry as a structure of thought rather than of external form, and we have to become familiar with the word ‘parallelism’. Hebrew parallelism juxtaposes thoughts in the form of phrases or clauses, which either reaffirm each other or contrast each other. In modern translations these thoughts are arranged in lines to look like poems but nobody knows for certain if this is what the Hebrew authors intended.

One type of parallelism in Hebrew poetry is called synonymous – the repetition of the same thought in different words, for example in Psalm 8:

I look at your heavens, shaped by your fingers,

At the moon and the stars you set firm –

what are human beings that you spare a thought for them,

or the child of Adam that you care for him?

And here is an example from the New Testament (whose original authors were also Hebrew): ‘For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light’ [Matthew 11:30].

Another type of parallelism is called antithetic where the first thought is contrasted by the second, for example in 1 Samuel 15:22:

Is Yahweh pleased by burnt offerings and sacrifices

Or is he pleased by obedience to Yahweh’s voice?

Here is an example from the New Testament: ‘Woe unto you that are full for ye shall hunger’ [Luke 5:25]

Constructive parallelism is where the second thought builds on the first thought: ‘This was the Lord’s doing, and it is marvellous in our eyes’ [Mark 12:11]. Chiastic parallelism, which we discovered in our reading of the first Creation story, is when the second parallel thought is inverted, for example:

For Yahweh watches over the path of the upright,

but the path of the wicked is doomed.

If you remove the chiasmus you get:

For Yahweh watches over the path of the upright,

but doomed is the path of the wicked.

Variations of these types of parallelism include Emblematic parallelism in which the thought is expressed half literally and half metaphorically, for example:

A golden ring in the snout of a pig

is a lovely woman who lacks discretion [Proverbs 11:22].

Climactic parallelism repeats short phrases towards some sort of climax, for example in Deborah’s victory song:

She reached her hand out to seize the peg,

her right hand

to seize the workman’s mallet.

She hammered Sisera,

she crushed his head,

she pierced his temple and shattered it.

Between her feet, he crumpled,

he fell, he lay;

at her feet, he crumpled, he fell.

Where he crumpled

there he fell, destroyed. [Judges 5:26-27].

The final word, ‘destroyed’ is climactic because it is the most powerful word and it has not been anticipated by repetition.

Translators who did not understand Hebrew parallelism would imagine that there were two killing instruments, a hammer and a tent peg, but they are poetic equivalents of the same thing. Another example of this kind of misreading occurs in the book of Matthew. Here the author’s typological treatment of Zechariah [9:9] results in the comical picture of Jesus riding into Jerusalem on two donkeys at the same time. The Old Testament prophet describes the king riding into Jerusalem as:

Humble and riding on a donkey,

on a colt, the foal of a donkey.

This is synonymous parallelism.

Another form of repetition, which occurs quite frequently in the Bible is anadiplosis, a figure of speech in which the phrase at the end of one sentence is repeated at the beginning of the next, for example

I will lift up mine eyes unto the hills, from whence cometh my help.

My help cometh from the Lord, which made heaven and earth. [Psalm 121:1-2].

Anaphora is yet another form of repetition common in the Bible. This is when the same word or phrase is repeated at the beginning of a clause or sentence. The most beautiful example is from Ecclesiastes, Chapter 3:

To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven:

2 A time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, and a time to pluck up that which is planted;

3 A time to kill, and a time to heal; a time to break down, and a time to build up;

4 A time to weep, and a time to laugh; a time to mourn, and a time to dance;

5 A time to cast away stones, and a time to gather stones together; a time to embrace, and a time to refrain from embracing;

6 A time to get, and a time to lose; a time to keep, and a time to cast away;

7 A time to rend, and a time to sew; a time to keep silence, and a time to speak;

8 A time to love, and a time to hate; a time of war, and a time of peace.

9 What profit hath he that worketh in that wherein he laboureth?

Listen to how Charles Dickens picks up these Biblical cadences in the opening sentences of his novel, A Tale of Two Cities:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times; it was the age of wisdom,

it was the age of foolishness; it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity; it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness; it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair…

He is using anaphora to capture the rhythm of carriage wheels turning.

Another poetic form, which occurs quite frequently in the Bible is the lament, my favourite being David’s lament for Saul and Jonathan. A lament is a poem expressing profound grief for the loss of something, a person, or a way of life. You’ll find these beautiful words in 2 Samuel Chapter 1:

19 | The beauty of Israel is slain upon thy high places: how are the mighty fallen! |

20 | Tell it not in Gath, publish it not in the streets of As'kelon; lest the daughters of the Philistines rejoice, lest the daughters of the uncircumcised triumph. |

21 | Ye mountains of Gilbo'a, let there be no dew, neither let there be rain, upon you, nor fields of offerings: for there the shield of the mighty is vilely cast away, the shield of Saul, as though he had not been anointed with oil. |

22 | From the blood of the slain, from the fat of the mighty, the bow of Jonathan turned not back, and the sword of Saul returned not empty. |

23 | Saul and Jonathan were lovely and pleasant in their lives, and in their death they were not divided: they were swifter than eagles, they were stronger than lions. |

24 | Ye daughters of Israel, weep over Saul, who clothed you in scarlet, with other delights; who put on ornaments of gold upon your apparel. |

25 | How are the mighty fallen in the midst of the battle! O Jonathan, thou wast slain in thine high places. |

26 | I am distressed for thee, my brother Jonathan: very pleasant hast thou been unto me: thy love to me was wonderful, passing the love of women. |

27 | How are the mighty fallen. and the weapons of war perished! |

The poetry of the Bible is nothing if not hyperbolic, that is deliberately exaggerated to impress the reader. Some hyperboles are obvious, for example: ‘Ye blind guides, which strain at a gnat, and swallow a camel’ [Matt. 23:24]. But there are others which are not so obvious and can be misinterpreted, for example: ‘All things are possible to him that believeth’ [Mark 9:23], or ‘If any man come to me, and hate not his father, and mother, and wife, and children, and brethren, and sisters, yea, and his own life also, he cannot be my disciple’ [Luke 14:26].

THERE FOLLOWS A READING OF MATTHEW 21: 1-7

Glossary

Metonymy: a figure of speech which puts one thing for another thing (or idea) closely associated with it e.g. calling the United States ‘Uncle Sam’, or calling a car ‘wheels’. In a sense, translations are metonymic because, regarding the Old Testament, English is put for Hebrew, and regarding the New Testament, English is put for Greek.

Inductive reasoning: arriving at a ‘truth’ by observing many particular instances. This is the scientific method. The opposite is deductive reasoning, which starts with a general ‘truth’ e.g. ‘There is a God’, and applies it to particular instances.

Dialectical: A process of argument where two opposing points of view (thesis and antithesis) are finally resolved (synthesis).

Immanence: The sense of a supreme being pervading the universe.

Binary: Something having two parts e.g. body and soul.

Analogy: A certain likeness in two things that is different in other ways. You can draw an analogy between a tree and an umbrella because they both give shade.

Typology: The study and interpretation of Biblical types, which show the fulfilment in the New Testament of Old Testament prophecies.

Cartesian dualism: Put simply: the idea that the mind is somehow separate from the body.

Redactors: Editors who have altered the Bible over hundreds of years, and established the canon.

Parataxis: Juxtaposing clauses and sentences without the use of subordinates. A paratactic style has the effect of abruptness e.g. ‘I win. You lose.’

Chiasmus: When the order of terms in the first of two parallel clauses or lines is reversed in the second e.g. :

The years to come seemed waste of breath,

A waste of breath the years behind.

[W.B. Yeats]

Continue the conversation about any of the above in the Poetry and Literature in Bulawayo Facebook Group

https://www.facebook.com/groups/371206022979786/