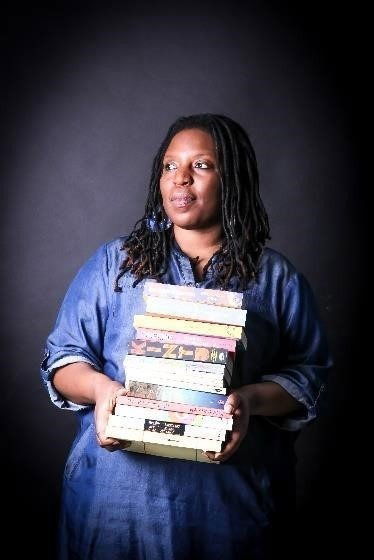

Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu in conversation with Drew Shaw in her hometown of Bulawayo, April 2021

Photo of Siphiwe Ndlovu by Joanne Olivier

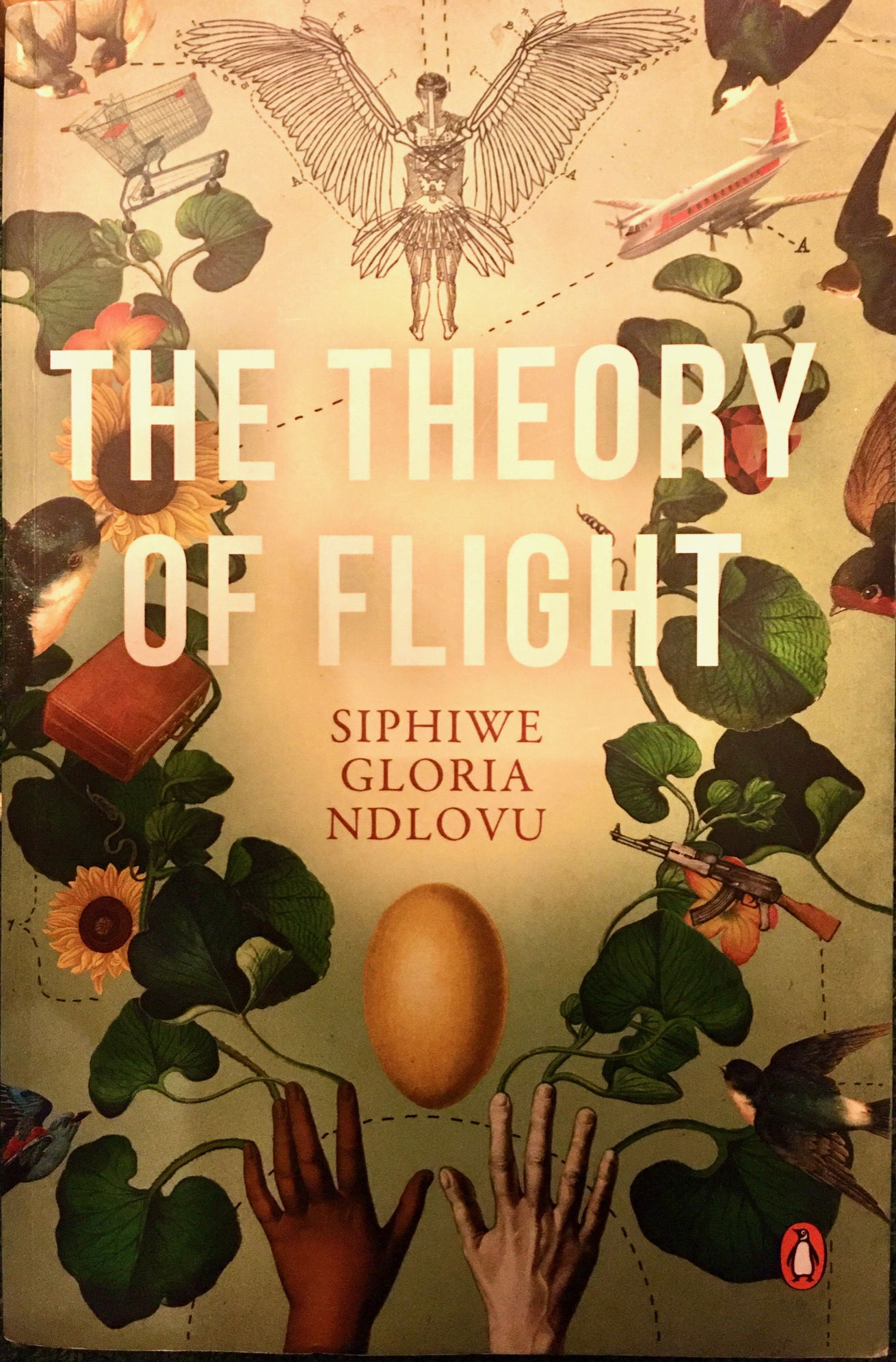

It’s wonderful to meet you, Siphiwe, in your hometown. First of all, congratulations on your two novels, The Theory of Flight (2018) and The History of Man (2020). They are published by Penguin South Africa and we are hoping they will become available here in Zimbabwe. You were also awarded a Morland Scholarship and are working on another novel; and you are also a filmmaker and hold a PhD in Modern Thought and Literature from Stanford University. Can you tell us a bit about yourself: where were you born, which countries have you lived in, what attracted you to film-making and creative writing and how did you end up doing a PhD at Stanford?

Thank you Drew. I was born here in Bulawayo in 1977. I believe we lived here for a few months after I was born and then we had to go to Sweden. My grandparents were politically active and so we became political refugees. After living in Sweden for a year, my family moved to the United States and after independence, probably end of 1980 or beginning of 1981, we came back to Bulawayo. We lived on a beautiful small-holding in a place called Rangemore and it was here that I fell in love with sunflowers. My childhood in Rangemore informed many events in The Theory of Flight, especially those that take place on the Beauford Farm & Estate. When I was eleven my mother and I moved to Hillside and it was from there that I did most of my schooling until I finished high school [at Girls’ College]. And then I went to the United States for university, and I was in the US for 18 years - in Boston, Massachusetts and then in Athens, Ohio, and then in Palo Alto, California. Then I came back to the continent and taught in South Africa for three years. In 2018 I decided to come back to Bulawayo.

As a child, I was very fortunate to have stories all around me – my grandparents had a library that had a decent collection of children’s books, the mobile library used to come to Rangemore regularly and my grandmother was a phenomenally gifted storyteller. In school my most favourite thing was writing compositions. When I was nine or ten (to save the walls from my doodles) my mother bought me a very hefty scrapbook so that I could write down my ideas – I filled it with stick figures and each page had a different family and a different story to tell (this later helped with story boarding in film school). Because storytelling was such an integral part of my life, I wanted to be a writer from a young age. But, I knew that I would have to have a “real” profession as well and so throughout high school I wanted to be a psychologist. And I remember running that idea past one of my teachers, Mr Poyah at Girls’ College, and he said, No, but you know, Zimbabweans are fine, they don’t need psychology, and I thought …Oh…I don't think so. [Laughter both] But, okay.

When I was applying to the United States for college, I remember looking through the majors and realising that there was such a thing as creative writing that you could major in. Psychology became a forgotten dream in that instant. So I went to the United States to major in creative writing. And while I was doing that, I took a class in screenwriting and fell in love with that. So then I went to film school. I just really loved being creative. I still do. I love telling stories. So that's what I have decided to dedicate my life to.

We’re glad you’ve returned to Bulawayo for a while at least. The Theory of Flight won the Barry Ronge Fiction Prize in South Africa in 2019 (which honours authors who enthral with their imagined worlds), and it’s not hard to see why you were recognised in this way. It’s magical in its innovations with language and narrative form. The Sunday Times Literary Awards panel described it as “utterly captivating and image-rich, a beautifully resolved magical-realist novel.” It is the first I believe of an intended quadrilogy?

Quadrilogy? I think we should just call it a series at this point. It's a series of interconnected novels… Through writing I have entered a world I don’t want to leave anytime soon. But, thank you so much for those kind words.

You deserve them. You have chosen grand titles. What’s the reason for that?

The History of Man is actually a critique of the colonial narrative and enterprise and this idea that knowledge can be complete. I'm playing around with the idea that anything can be that definitive: ‘The History of Man’. Because what we have received as “History” is obviously very limited in terms of narrative and perspective, The History of Man is focalised through a character, Emil Coetzee, who has a very narrow perspective. So, as you read the novel, you realise that the protagonist’s voice, the protagonist’s point of view, is all that you get. And that, for me, is an experience that I have when going to the National Archives, our archive in this country is very black and white… where anything before 1980 is mostly white … and anything after 1980 is mostly black. Therefore, for anyone interested in history, there is no access to the full story because of the various erasures, silences and omissions that occurred during the making of the archive. Intellectually and creatively I'm very interested in the erasures and the silences that are extant in the colonial and postcolonial narratives. And so that's why I have this very grand title for my story that is about the colonial narrative – The History of Man. There is an obvious irony here. The narrative doesn’t even come close to being as all-encompassing as it sounds.

The title The Theory of Flight was not a little influenced by the fact that I was a PhD student at the time. So the ‘theory of’ something is in the title. There are many instances of ‘flight’ in novel: the protagonist, Genie, flies away; her father, Golide Gumede, builds a pair of silver wings; the silver wings, in turn, create a race of angels; at a certain point Genie has to escape from the Beauford Farm & Estate; various characters fly in and out of the country. The novel also treats ‘flight’ as a symbol and metaphor for liberation or self realisation or freedom of the self. I really like the different ways that the idea of flight is played around with in the novel. The title, The Theory of Flight, is all-encompassing in a different way from how The History of Man is all-encompassing and ‘Flight’ can actually be about all these different ways of thinking about life and being.

That’s apt. Thank you… Your protagonist, Emil Coetzee, in The History of Man, admires colonial ‘men of history’ such as Frederick Courtney Selous. And Emil’s masculine sensibility is shaped by authors such as Rider Haggard, Rudyard Kipling and Joseph Conrad. Manliness and empire-building are themes, also, in other writers from the region. I’m thinking of Wilbur Smith’s Men of Men. And your novel picks up the conversation on this subject with an apparent confidence. Did you have to do a lot of background reading and perhaps archival research? And was it hard to find a voice, to edge your way into a colonial-styled, male-oriented arena?

For any novel I write I do research and try to read as much as I can on the subjects I will be writing about. I am lucky in that I have been doing archival research now for over fifteen years so I have already collected quite a bit of information about this country’s history. I read Haggard and Kipling as a child, and I read Conrad in college after reading Chinua Achebe’s critique of Heart of Darkness. I have taught Conrad at both the college and high-school levels. Also as a postcolonial scholar this is a world that I am very familiar with. My dissertation also looked at Rhodesian authors, so for many years now I have been reading, analysing, critiquing texts – fiction and non-fiction – that deal with this world and so when I started writing The History of Man I already had a wealth of information at my fingertips. I thought it would be difficult to inhabit that ‘colonial-styled, male-oriented arena’ as you refer to it…I thought it would be difficult to find Emil’s voice. But the truth is that it actually wasn’t difficult to inhabit that world and find his voice. I just had to be very careful not to slide into caricature and/or stereotype – I think in the end that was where the real danger lay. I had to make Emil a full character with an interiority that was easy to access, make sense of and understand. Although Emil exists within the colonial narrative, it is important to note that many of the attitudes that I am depicting have survived well into the postcolonial era. I went to Girls’ College in the 1990s and Coghlan Primary School for two years in the 1980s and witnessed a lot of these attitudes on display. Because I experienced them myself I found them relatively easy to write about. In case we think otherwise, these attitudes are still with us in 2021.

This is true. Yes, the Selous School for Boys in your novel actually reminded me, in some respects, of Falcon College, which I attended in the 1980s. I think we live with the legacy of the colonial narrative well into the twenty-first century. But your novel comments subtly, critically, intriguingly about it, and the characters are finely observed. I’d like to ask about your character Scott Fitzgerald who reminds us of the well-known American author. Was the allusion deliberate and, if so, why?

Most definitely. I remember reading an article that speculated on what America would have lost had F. Scott Fitzgerald, author of the Great American Novel, died during World War I. And so, for The History of Man, I created a character, Scott Fitzgerald, who is a budding but unpublished writer who goes to war and is killed. What was he working on? Could it have been the Great Rhodesian Novel? What would the Great Rhodesian Novel have been like? I think this taps into a fear that writers have – I know I definitely have it – what happens if I die before completing my manuscript. For first-time authors the fear is, perhaps, compounded and more pronounced because there is already the spectre of ‘manuscript never published’ hanging over you and your work. What is it that we lose as a reading public when certain works don’t get published? What does the canon lose? What does a ‘national’ literature lose? What does the world of literature lose?

Interesting! Continuing with memorable characters, in The Theory of Flight the story is centred on the life of the magical Genie – loved by all - but as you say in the Prologue,

'What happened to Genie did not happen in a vacuum: it was the result of genealogies, histories, ideologies, epistemologies, and epidemiologies - of ways of living, remembering, seeing, knowing and dying.' (p. 9).

You’re clearly interested in the overarching story of an unnamed southern African country, which has seen civil wars, struggles over land, mass migrations, displacements, genocide, economic meltdown, an HIV/AIDS pandemic, and power struggles. And I recall Dambudzo Marechera, an early anti-realist in the region, said, ‘For me the point is if one is living in an abnormal society then only abnormal expression can express that society. Documentary cannot.’ Do you agree? Did you feel straightforward realism was inadequate for the story you wanted to tell in The Theory of Flight?

You know, I’ll say Yes and No. I think the reason I chose to use what people call ‘magical realism’ and to focalise the story through all these characters instead of one central character, was because I was trying very hard to depict and showcase the diversity that exists around a person. Most stories come from a very real place and I like it when academics turn everything into a theoretical thing it [light laughter]. And I’m like no, no, no [laughter]. So the real place that the story comes from is … I lost someone that I loved very much – my aunt. And while attending her funeral, I realised that everyone remembered her very differently; and that's part of what I was trying to capture. Also, what I was trying to capture was this postcolonial moment, where you have all these different voices, and different experiences coming around a central thing in this case around Genie’s life and death. I feel like most of the Zimbabwean fiction that I've read, or that I’d read up to that point, didn't really do a lot with diversity and different voices and experiences. And that really bothered me because it seemed like Zimbabwe was very comfortable with segregation and with continuing to segregate voices and experiences within a work of fiction, and that for me was really limiting for the story that I was trying to tell. Going back to what Marechera said, I think, yes, it can be very difficult to write a ‘normal’ story for an ‘abnormal’ society, but it can also be very… freeing. The History of Man is very much a realist novel that is chronologically told, and as I said before, focalised through one character who is the central character, and yet the story is very much about an ‘abnormal’ situation and society. So that's why I said Yes and No in the beginning, because I think you can do both. I think it depends what your ultimate goal is and what you are highlighting about the situation you are writing about.

Interesting! At the moment we are mindful of social distancing because of a global pandemic, but it’s not the only pandemic to have beset southern Africa. I’m referring to the HIV/AIDS pandemic, which strikes characters and causes tragedy in The Theory of Flight. Can you say some more about it. Why did you want to address HIV/AIDS (which was devastating in this country as you know) in your first novel? And what might be the advantage of addressing it in a so-called ‘magical realist’ manner?

I’ll come out and say it. I don’t really read The Theory of Flight as a magical realist novel, or, perhaps I should say, as only or primarily a magical realist novel.

I realise, yes, it’s sort of a label, an unfortunate tag [laughter both]. Can I ask you what genre you would prefer it to be described as?

You know, I think it's partly a work of historical fiction… a work of literary fiction… I'm more comfortable with those labels. I personally love magical realism, but I find that it is a label that can obscure some of the other things happening within the novel/story and that, therefore, because of this it can become a very limiting label. More importantly, what is deemed “magical” vs what is deemed “real” seems to be the concern of a particular literary tradition – not all literary traditions treat these things as binary opposites – dichotomies.

In The Theory of Flight I was trying to capture the time and place that I grew up in, which was a time and place that, as you said, was beset by the HIV pandemic. At a certain point the statistic was one in four adults have HIV, and so for post-independence Zimbabwe HIV was something very real, very immediate and very frightening. And I wanted my first story to capture that. Now I know that, you know, there's a lot of ideas around Africa and there are a lot of value judgments about African fiction and the idea of doom and gloom – African literature is too political, is all about these horrible things that happen etc. But how do you tell the story of this time and place without talking about the pandemic? HIV was for my generation, at least, one of the things that definitely defined us – we had relatives who had it, some of us grew up to have it, we lived under its constant shadow, whether we acknowledged it or not it shaped us in many ways. So I didn't want to tell a story that doesn't deal with HIV when it was such a very pivotal thing in all our lives.

And then the question about the magical realism, and why I chose to tell a story with ‘magical’ elements. It was also to capture this particular moment in Zimbabwean history, because I used to read the newspaper as a child and if I remember correctly, there were stories about this person called ‘Jane the Ghost’, right?

Stories of Jane the Ghost, for those unfamiliar, featured in Bulawayo’s Chronicle newspaper. She was seen as a prostitute, in the late 80s and early 90s, who would suddenly disappear, leaving patrons abandoned and mystified - an example of the supernatural meeting the everyday.

Yes. So for me, there was this very thin line between what was real, and what was fiction. And if you can read a story about a ghost in a newspaper, that says a lot about the time and place that you live in. If you can receive stories about the liberation struggle that make people seem like shapeshifters, or people that can just make themselves disappear into thin air, then for me, as a writer, part of my job is to capture all of that, because that says something about the creativity of the moment. It says something about our imagination in that moment in time. And I wanted to really capture that. Now, you know, in The Theory of Flight, you have characters flying away and all that's, yes, partly magical realism, but also, partly, for me, the realisation that in this time and place anything is possible. What I like about the 80s and 90s – at a time when we are still reeling from a civil war and we have a genocide and a pandemic – is that people still had so much hope, and still were willing to think (not everyone obviously) beyond the limitations of the time and place that they were living in. And for me, that's something that was brilliant. I don't think it's something that's there right now -- today. Or if it is there now, I'm not able to find it, but I feel like that was something that was there then. People, perhaps because independence was so recent, had this understanding of themselves as being capable of more than what was thought possible.

And so for me, it's important to capture that particularity and peculiarity of the 80s and 90s. So yeah, I feel like I was just trying to be very, very true to the moment that I was writing about in that sense. I do like it that Genie is able to do a “magical” thing and fly away. I like playing around with all those things, but I also just wanted to capture the possibilities that were there at the time. For me the flying is ultimately about this deep and strong belief in yourself and what you’re capable of, which I think we don't get socialised into having in this country because it is seen as posing a danger to the state. We are socialised to be dependent, not necessarily realising that we always have this power within us. And I think Genie is a person who realises that she has that power within her and is able to show people around her this absolute belief in the ‘self’.

Absolute belief, yes, and that’s powerful. I was going to say I think The Theory of Flight is unique in Zimbabwean literature. And I'm going to claim it for the national literature, even though it's set in an unnamed country. Although there are other writers who attempt to blend fantasy and realism, I think your book stands out. You literally have a character who flies away with a giant pair of silver wings. For me, unlike other non-realist novels, yours is on an epic scale, on a very broad canvas. We were talking about Marechera experimenting with anti-realist forms. Yvonne Vera does the same. There are other writers who've attempted with non-realist forms, to write novellas or shorter pieces, but what strikes me about The Theory of Flight is its grand scale. This strikes me as a way of retelling history in a refreshing new way. It's not linear, but it makes sense.

Can I also just add that part of what happens with that history that has erasures and silences and omissions is that it then allows for what I suppose people then call the magical to exist, right? Because you then are not necessarily bound by what is seen as necessarily real or rational…you can still play with some of what came from the oral tradition, which is all these other things... So there are fables, right, and what's possible with translating a fable into real life. Because you're not necessarily bound by this idea, this binary of ‘this is what's real’, ‘this is what's fiction’.

And fables are very much part of literary traditions, and you draw from several others, including the epic. And this maybe speaks to your discomfort with the label magical realism. Because it doesn’t sum it up entirely.

I think that part of what I am always trying to push against with the magical realism label is that, it is one way to read the novel. It's not the only way to read the novel. And I think when people label something so quickly, it can also disallow those other ways to be seen or to be talked about. So I think part of me pushing back is not because I don't see the magical realism. It's just that I don't want it to be labelled purely as magical because there's a lot else.

Can I ask you also about symbolism in the novel. There are many allusions, noticeably biblical allusions. Part One starts with a chapter titled Genesis. Then you have Genie, a miracle child, who hatches out of a golden egg and reminds us of an immaculate conception, and she’s quite angelic. Her name evokes the Genie trapped in Aladdin’s lamp, who grants wishes. Then there’s the character Jesus who saves Genie’s life by a miracle. And finally you have Genie rising from the dead and flying away. There’s transgression and tragedy on an epic scale, yet also a message of hope and, for me, possible redemption. Can you talk about your use of symbolism. What were you trying to do?

I think the framing of your question already answers your question about symbolism so I, thankfully, don’t have to think of something intelligent to say on that score. Yes, the first chapter is Genesis and the last chapter is Revelations so there is a definite allusion to the Bible. For me, the Bible is a book that tells the history of a people and acts as a document and an archive. Yes, it does get co-opted into being the basis of a particular religion, but at heart it is the history of a particular people. I thought, wouldn't it be nice to just tell a story of these people (in a different place and time) in a way that mimics that.

As a historian, or someone who loves history, what always worries me … especially [for] people my colour, in this country, and on this continent, and all over the world is that during long moments of modern history we were reduced to chattel, slave, native, 'boy', ‘invisible or problematic’ woman – we didn't have to have a name, we didn’t have to have useful thoughts or knowledge, we didn't have to have a personality – we were exploitable things and as such did not have to be part of the archive as anything but a statistic. We didn't matter. So now as inheritors of this history we don’t have much access to black people’s experience of it because of those erasures, silences and omissions that I spoke of earlier. So this is what we inherit as people, we inherit a past that is, if you're lucky, you have it orally, but you don't have it in a written form. And that’s not to say that the written form is better than the oral. We also have lost part of that oral tradition because of the written form and because of the movement that has happened in the modern era. So it's like we're in this unenviable, catch 22, rock and a hard place space.

So I wrote The Theory of Flight in order to make connected (not full or whole) this history that has a lot of omissions, a lot of silences, a lot of erasures. In the novel you have histories that start and then stop abruptly – interrupted histories. You have the story of the grandparents meeting and then the grandfather just disappears into the Indian Ocean, and then the story moves on - because that's exactly how a lot of us receive those moments, our histories as incomplete stories. For instance, I don't have the complete story of my great-grandparents in any form because our oral history has had to survive through migrations, displacements and diasporas. So I really wanted to have and to give these people who had had this … always interrupted history, something of a more connected story. Something that mimics what happened in the Bible, which is, you know, so and so begat, who begat, who begat, who begat, which then gives us a genealogy… a history. The novel might be pointing towards a liberation theology of sorts, but that is for the reader to decide.

Well, it’s a genealogy at least, a history from Genesis through to Revelations…

So, yes, the biblical allusions are very intentional. But I also wanted to show that history in this place cannot be this complete thing because of the interruptions… There’s precolonial movement and displacement, there's colonisation, there's removing people from their ancestral land, there's this civil war, there’s postcolonial genocide, there’s political unrest and economic failure and the resultant diaspora. All these things, all these interruptions cannot allow for a very linear full story, but they can still allow for a story, and that's our story… our history.

The patchwork of interlinked stories makes sense in that respect…Speaking about interlinked stories, The Theory of Flight and The History of Man are such different novels in many respects, yet interlinked by some common characters: e.g. Emil Coetzee, Kuki Sedgwick, Everleigh Coetzee; Bennington Beauford, Beatrice Beit-Beauford, Vida de Villiers, Eunice Masuku and the young Dingani. (I may have missed a few.) Why did you want to connect these two novels in this manner? And will we meet familiar characters again in your next novel?

As I mentioned earlier, I am working on a series of interconnected novels. The novels tell the story of a community that resides in the City of Kings. The novels deal with different historical moments – precolonial, colonial, postcolonial, diasporic and global – and the impact of these moments on the community and the City of Kings. I think it makes sense to me to write like this because of my interest in history – through the novels I will be examining the metamorphosis of a place and its people over time. So, yes, we will meet certain characters again in other novels and definitely in the third one. Sometimes a character will have a major role in one novel and a minor role in another. For instance, Emil Coetzee is a minor character in The Theory of Flight, but he is the main character in The History of Man. This, for me, also depicts how we experience life – while we are the heroines and heroes of our own life stories in someone else’s life we are a lost love, a friend that one has lost touch with, someone that the heroine / hero sat next to on a bus once, someone that the heroine/hero didn’t even notice when they walked past. In life we are both major and minor characters.

This is so true… The other thing I wanted to ask you about is travelling and the issue of belonging in The Theory of Flight. It seems to be a novel of constant motion. We've got Genie flying away with a giant set of wings, we've got Baines Tikiti, Genie's grandfather who wanted to be a great explorer, travelling to the Indian Ocean, we've got Genie's father Golide traversing the Zambezi River, crossing in and out as a guerrilla fighter. And you've got Genie's adopted family, the Masukus, moving to America, and travelling back and forth, and you've got another character, Vida, becoming a famous sculptor, flying to and from Scandinavia. Then you've got the Beauford Farm and Estate as a site of revolutionary change, kind of charting the nation's troubled rural history in a way. You've got violence, you've got people settling, then fleeing and others settling again. So there's a lot of travelling and movement and that raises the question of belonging. I'm thinking where do the characters all belong? Because it's as if they exist in transit in many respects, uprooted and then resettled, and there's this feeling of susceptibility to sudden change, displacement, transience, but on a grand scale, you know, because it covers so many years, the novel, and it's quite epic.

Interestingly, one of your characters, Krystle Masuku, Genie’s adopted sister, is writing her PhD in America on the issue of travelling and belonging. Her American sister-in-law, trying to understand it, says:

‘It’s about the history of your country, how it was never able to become a nation because the state focused belonging too singularly on the land. In colonial times it was attached to being a settler and in postcolonial times it is attached to being autochthonous. This means that throughout your country’s history there has always been some group or other that has not been allowed to share in the sense of belonging.’ (p. 278)

There’s a sense that all of the characters, actually, belong somewhat awkwardly, whether they are in the diaspora in America or on the ground in the unnamed country. Would you say this is true?

Yes. And I think you know that the dissertation that Krystle is writing is actually my dissertation. For me, that's my understanding of this country. I don't know if it's unique to this country, but I think one of the things that we missed at the very, very beginning, sort of like at the moment of encounter was the fact that we were encountering each other. So people were coming from elsewhere. And instead of thinking about how we were going to build something together, as all these people coming in and moving, it was sort of like, you know, We're the settlers, so we now belong, and you don't quite belong, because you are native and primitive and we, the settlers, are civilised and our more modern ways can best create and shape the country and we know this to be true about ourselves because look what we can do with the minerals we mine, with the produce we grow, with the animals we rear – look how we can use these things to make our country great. And then belonging all became too focused on the land and what could be done with it. This exclusive way of thinking about belonging is just so limiting and limited.

For me, the one thing that seems to connect us - because I don't like the idea of focusing belonging on land, because that's very exclusive (some people belong, some people don’t)…What I think brings us all together is this idea of travel, that we all, for different reasons, are moving in and out or within the country. In a country where different ethnicities are seen as residing in particular places, to move from one place to another is as big a deal as actually crossing a border and going to another country.

And so when I look at Zimbabwe's history, or Rhodesia/Zimbabwe’s overall history, I see a lot of movement. I see, before the settlers came, there were the Matabele, my people, coming in because of what was happening in South Africa [during the mfecane period of political disruption and migration]… The autochthonous people here are, we all know, the Khoisan. Everyone else has come in from elsewhere and settled here – we need to be honest about this. The Khoisan moved around a lot, as we can see from [rock art, etc.], so for me this idea of movement is actually what brings us together – it is the character of this country.

If we could actually build a sense of identity and belonging around a history of movement, then I think it is a more inclusive and sustainable way of thinking about the Zimbabwean… being Zimbabwean… belonging to Zimbabwe. Instead of saying, these people came and took the land, or these people came from over there and settled here, and they don't really belong. That doesn't help the issue. I don't think it's meant to help the issue. I think it's meant to actually divide us. But what could bring us together is this idea of belonging that is based on travel and I think we belong awkwardly because our belonging is never settled. Like, right now, I can think that I'm going to be here for the next two years, but something might happen and then I find myself in the United States for the next 10 years, you know, but part of me is always going to still be Zimbabwean. We have a huge diaspora right now… a Zimbabwean diaspora all over the world. So I just really like the idea of thinking about the past 150 years, or however long it's been, through this idea of travel, and travel being this thing that encompasses a lot of different kinds of movement… We all come and we create a nation, whether we like it or not. What that nation is, is reflected back to us, and I think we've never wanted to see that – our diversity.

So we always focus on the land, because we don't want to necessarily see the diversity of who we are. Because it's too, I suppose too fraught to actually think of ourselves as a people that have come together from different places. But I think that's the way forward. So in my novel, I replicate that with all the people moving around the way they do.

Yes, it's a perspective that rings true. And I was led to your PhD dissertation by that character, actually. It’s titled, “‘A Country with Land but No Habitat’: Travel and Belonging in Colonial Southern Rhodesia and Post-Colonial Zimbabwe” (2013) and in it you study Rhodesian and Zimbabwean writing over a century or more (authors such as Sheila MacDonald, Cynthia Stockley, Doris Lessing, Dambudzo Marechera, Charles Mungoshi, Tsitsi Dangarembga, Yvonne Vera, Brian Chikwava) and in text after text you advance a consistent argument about travel and belonging. As you say:

'This history of constant movement has shaped the country, its people’s sense of belonging, as well as their political and creative imagination… What all this movement and travel has resulted in, I will argue, is a sense of “belonging awkwardly”, to borrow a phrase from David McDermott Hughes, that is shared (whether acknowledged or not) by all those who inhabit this space and reveals itself in the creative imagination of those who inhabit the country and its diasporas.' (p.5)

You draw on David Hughes’s Whiteness in Zimbabwe (2010), where he argues the white settler population has tried and failed to properly ‘belong’, going to extraordinary lengths, such as constructing dams and waterways, to better identify with the landscape, to ‘Europeanise’ it in a sense. But what’s most interesting about your analysis is that you extend that concept to a broader understanding of all Zimbabwean literature - both black and white, turning Hughes’s central argument on its head in many respects, because it seems you are saying everyone - not just the white community - ‘belongs awkwardly’ - and that this will remain true as long as we all hold onto a land-based concept of Zimbabwean identity. So that's an attempt to understand it from an academic angle, and we can see it in your fiction, but as you as you point out, yours is not alone. It’s a theme throughout the entire national literature, and there’s certainly more to discuss for another time.

There’s a recent book by another Bulawayo writer, Sue Nyathi, called The Gold Diggers [which is about Zimbabweans seeking fortunes in South Africa]. It seems maybe this next generation of writers is going to deal more with this idea of travel and belonging.

Yes, I believe so. Thanks for sharing your insights, Siphiwe.

It is my pleasure, Drew. Thank you for the wonderful conversation.